- "Bloodbath" In Black Gold – Buffett's Phillips 66 Dumps Oil In Cushing, Crashes Crude Spreads To 5 Year Lows

The canary in the coalmine of an increasingly desperate energy industry just croaked. With "unusual timing" and at "distressed prices," Reuters reports that Phillips 66 – the major US refiner owned by Warren Buffett – dumped crude oil for immediate delivery into Cushing storage tonight. This sparked heavy selling of the front-month WTI contract (to a $26 handle) and crashed the 1st-2nd month spread to 5 year lows.

It was just last week when we said that Cushing may be about to overflow in the face of an acute crude oil supply glut.

“Even the highly adaptive US storage system appears to be reaching its limits,” we wrote, before plotting Cushing capacity versus inventory levels. We also took a look at the EIA’s latest take on the subject and showed you the following chart which depicts how much higher inventory levels are today versus their five-year averages.

And now with Reuters reporting on major US refiners dumping crude, sparking speculation that the move reflected advance warning of looming output cuts amid sluggish winter demand and record inventories…

Front-month WTI collapsed to a $26 handle…

The unusual sales of excess oil crashed the March/April WTI futures spread… One trader described the market as a "bloodbath."

It was unclear how many barrels one of the largest U.S. independent refiners sold, but three traders confirmed at least two deals traded at negative $2.50 and $2.75 a barrel. Two sources said a second refiner was also looking to offload barrels but transactions were not confirmed.

These deals drew notice among traders, who said the prices were distressed and the timing unusual… sending the cash-roll to 5 year lows…

The so-called cash roll, which allows traders to roll long positions forward, typically trades in the three days following the expiry of the prompt futures contract. The trading period for February-March contracts concluded almost three weeks ago.

Since then, however, oversupply has pressured refined products prices lower, and now some grades of crude are yielding negative cracking margins, traders say.

"Midwest margins turned negative after operating expenses last week and forward cracks suggest margins will remain in the doldrums for some time," said Dominic Haywood, an analyst for Energy Aspects in London.

If Phillips 66 does cut refinery runs, it would be the third refiner to capitulate amid record gasoline inventories and negative margins.

Earlier on Wednesday, sources said Delta Air Lines' Monroe Energy refinery near Philadelphia had decided to cut output by 10 percent at its 185,000 barrels per day (bpd) refinery due to economic reasons.

On Tuesday, sources said that Valero Energy Corp was planning to cut gasoline production at its 180,000 bpd Memphis, Tennessee, refinery by about 25 percent.

U.S. Energy Information Administration data on Wednesday showed inventories at the Cushing, Oklahoma delivery hub hit a record 64.7 million barrels last week – just 8 million barrels shy of its theoretical limit – stoking concerns that tanks may overflow in coming weeks.

And so, with the news that Phillips 66 is dumping in apparent size, it appears, as we detailed previously, that BP's warning that storage tanks will be completely full by the end of H1

"We are very bearish for the first half of the year," Dudley said at the IP Week conference in London Wednesday. "In the second half, every tank and swimming pool in the world is going to fill and fundamentals are going to kick in," he added. "The market will start balancing in the second half of this year.”

May be coming true a lot sooner.

- Is The US Leading Saudi Arabia Down The Kuwaiti Invasion Road?

Submitted by JC Collins via PhilosophyOfMetrics.com,

For the first time in a long time I feel concerned and worried about the prospect of war. The reaction of Saudi Arabia to the Russian intervention in Syria has always been the wild card in the shifting geopolitical power base in the Middle East. Turkey and Israel, along with Saudi Arabia are the three countries with the most to lose because of a strong alliance between Syria, Iran, Hezbollah, and Russia.

These three traditional American allies have been accustomed to Western support in regards to their own specific regional goals and ambitions. This support has been so staunch and counterproductive to regional stability that the growing comfort and alliance between Iran and the US should be both confusing and worrisome to Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

On the one hand the US is making agreements with Iran and lifting sanction while on the other hand it is indirectly supporting Saudi Arabia’s and Turkey’s proxy war against Syria. A war which Iran, along with the support of Russia and Hezbollah, are resisting and countering with massive aerial and ground support.

This contradiction is suggestive of another and more complex strategy which may be unfolding in the Middle East. A strategy which is beginning to look familiar.

Back in 1990 when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait the state of the Iraqi dictator’s mind was both paranoid and desperate. The once American supported leader at some point felt he would have the blessings of the US administration in his regional adventures. The controversy surrounding US Ambassador April Glaspie’s comments to Saddam regarding having no interest in Iraq’s border dispute with Kuwait, and her later vindication by the release of a memo, is somewhat irrelevant as Saddam obviously felt the support was there. Whether through direct and straightforward communication or through trickery.

Once Iraq invaded Kuwait the Western press mobilized and a massive propaganda campaign against Saddam Hussein commenced. The once American ally was isolated on the world stage and suffered one of the worst military defeats in the history of warfare.

The interesting parallels between 1990 Iraq and 2016 Saudi Arabia are unlikely to be coincidental. Both have militaries which were built with American equipment and support. Both were used by American interests to counter Iranian regional ambitions. Both supported the sale of their domestically produced crude exports in US dollars.

In support of this conclusion we find the recent statement of Iranian Armed Forces’ Chief of Staff Major General Hassan Firouzabadi, who stated:

“US Defense Secretary [Ashton Carter] is supporting and provoking the House of Saud to march to the war [in Syria]. This is an indication that he is at a loss. It also proves beyond any doubt that they have failed.”

Are we to assume that the US strategy in the Middle East is at a standstill? I seriously doubt that and America’s agreements with Iran would support something else being afoot. America may be misleading Saudi Arabia down the same road as it led Saddam Hussein in the buildup to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Except this time the aerial bombardment will come from Russian forces and the mop up crew will consist of Iranian and Hezbollah forces.

Further support for this conclusion comes from the recent comments of John Kerry where he said “what do you want me to do, go to war with the Russians?”

Why is there this disconnect and contradictory approach within the American government? I seriously doubt that it is caused by opposing factions within the US establishment. A potential war of this magnitude will not be left to the whims of domestic bantering and browbeating.

Saudi Arabia and Turkey are both pushed into a corner over the shifting power base in the Middle East. The paranoia and desperation, like Saddam in 1990, could very well cause both countries to commit to the very act of aggression which will lead to their ultimate demise and removal from a position of influence within the region.

Are we on the verge of another war?

Perhaps. But I still content that it will be a regional war only and that the objective of that war will be the removal of once American allies who have been funded and provided with the equipment which will now have to be destroyed and removed from the region.

In the post The Coming Islamic Revolution in Saudi Arabia I wrote the following:

“There is a growing consensus that there may be a division within the Saud family itself. This is the one thing that could very well finally topple the monarchy. The House of Saud could be tearing itself apart with opposing strategies.”

“One strategy is based on maintaining socioeconomic and military control over the country, and working with other nations, such as China, on developing business contracts which are not based on crude, but on other sources of revenue which can be gained from alternative energy sources, such as nuclear.”

“The other strategy involves a conclusion where the Shiite majority which is building up around Saudi Arabia will eventually incite revolution within the country as the conflict in Yemen spreads further across the border, and deeper regional integration between the Shiite players takes place.”

It is plausible that an overthrow of the House of Saud would benefit the American strategy against China. The divisions within Saudi Arabia make it ripe for such a strategy explained above. Especially if there is a faction of the House of Saud which would be willing to take control of what remains and fit within a larger Middle Eastern regional alliance.

A negotiation with China regarding crude sales in renminbi as discussed in the post The Petro-Renminbi Emerges, could very well be the macro-geopolitical and macro-socioeconomic strategy which is unfolding here. Such an outcome would benefit both China and Russia, while also maintaining a check on Iranian regional ambitions.

To think that the US would enter into a major war against Russia over Saudi Arabia is fraught with mindlessness and madness. The more probable strategy is the overthrow of the House of Saud, or at least a complete restructuring of the countries place within the Middle East.

Will Saudi Arabia take the bait and invade Syria? I think we may know that answer sooner rather than later.

- This "Stunning" Chart Shows How Quickly Europe's Refugee Crisis Is Accelerating

Earlier today, we reported that European officials are considering a two year Schengen suspension to help stem the inexorable flow of Mid-East migrants into Western Europe.

Last year’s optimism regarding the bloc’s ability to take on asylum seekers quickly faded as eurocrats suddenly realized just how daunting a task they’re facing. Even if the integration effort were going smoothly, the task would be well nigh impossible. Germany, for instance, took in some 1.1 million refugees in 2015 – the country only has 82 million people.

Of course the integration effort isn’t going smoothly at all. A wave of sexual assaults blamed on men “of Arab origin” swept the bloc on New Year’s Eve and since then, a rising tide of nationalism threatens to destabilize the entire region and thrust the likes of Germany, Sweden, and Finland into social upheaval.

To understand just how acute the problem is, consider the following chart from The Washington Post which shows how many more asylum seekers fled to Europe from January 1 through February 7 of this year compared to the number arriving from January 1 to February 28 of 2015.

And if you think it’s bad now, just wait until the weather warms up.

As one unnamed German official told Reuters last month, “Europe has until March, the summer maybe, for a solution. Then Schengen goes down the drain.”

We’re going to need bigger fences…

- Putin Uses the Refugee Crisis to Weaken Merkel

“Putin Uses The Refugee Crisis To Weaken Merkel“, by Judy Dempsey as originally published at Carnegie Europe,

Back in December 2015, when it became clear that refugees from the Middle East would continue to head toward Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel reassured her conservative Christian Democratic Union party that everything was under control. All she needed, she told party members, was more time. Germany could manage the influx of over 1 million refugees and asylum seekers.

Merkel was banking, naively or not, on two things: peace talks that would end the five-year-long war in Syria; and cooperation from Turkey to stop sending refugees to EU countries, improve the conditions for refugees, and strengthen the EU’s external border. Neither has materialized. Merkel’s task of reassuring her party and voters is becoming trickier by the day.

The peace talks in Geneva aimed at ending the Syrian war collapsed on February 3. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon blamed Russia. On the eve of the talks, Russia had bombarded the rebel-held city of Aleppo. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s forces were back with a vengeance. So much for those Western leaders who believed that Russian President Vladimir Putin was an essential partner in weakening the so-called Islamic State and ending the war in Syria.

Putin’s policies in Syria have wreaked further havoc in the region. During the weekend of February 6–7, tens of thousands of refugees were trying to flee to Turkey, itself in the throes of a war with the insurgent Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Many refugees will try to make it to Europe rather than remain in Turkey. As the war in Syria continues relentlessly, Merkel is coming under siege from all sides, no thanks to Putin and no thanks to her EU counterparts.

Putin’s continuing support to keep Assad in power has a direct correlation with Merkel’s weakening support at home. The longer the war in Syria endures, the weaker it could make Merkel. This has consequences for the rest of the EU. A weakened Merkel means a weakened, more divided Europe. The bloc will be in no shape to deal with the ever-mounting security challenges it faces, not least the ongoing political crisis in Ukraine, where on February 3 the economy minister resigned in disgust and frustration over corruption.

Against such a background, it is going to be very hard for Europe’s most powerful leader to try to swing the mood in her country. Germans are increasingly skeptical of her slogan “Wir schaffen das!” (“We can do it!”) and increasingly critical of other EU countries’ refusal to accept the moral, political, and humanitarian principle of taking in those fleeing war.

Yet this is what EU governments will have to do if they want Turkey to help protect the EU’s external borders. “Europe can’t completely keep out of this,” Merkel saidduring her weekly podcast just before she headed off to Turkey on February 8.

Merkel’s latest plan is for Turkey to stop the flow of refugees to Greece, which can no longer cope under the immense strain. But outsourcing the refugee problem to either Greece or Turkey is not a sustainable option. In return for Turkey’s assistance, Merkel said EU countries, many of which have already refused to take in refugees or are closing their borders, would have to be willing to accept quotas of migrants. They must share the burden of providing shelter to refugees with Turkey, which has taken in over 2.5 million people fleeing Syria.

“We need to protect our external border because we want to keep Schengen,” Merkel said, referring to the system of passport-free travel among most EU countries. “And if we can’t protect it, then this huge region of free movement, our internal market, which is the foundation of our prosperity, will be in danger, and we need to prevent that.”

But one has to wonder if those political parties and movements opposed to giving refugees shelter actually care about Schengen—and, as a corollary, about the EU. This is Merkel’s other problem.

Month by month, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) is creeping up the opinion polls. Once a bourgeois Euroskeptic party, it has shed its sheep’s clothing. It is now becoming a home for the far Right. The more EU countries refuse to take in refugees, the more the AfD can tap into this dual anti-Europe and anti-refugee sentiment.

This is not lost on Merkel and her coalition government. A poll published on February 3 by the German public broadcaster ARD showed several worrying trends for Merkel. The government’s popularity has fallen from 54 percent in August 2015 to 38 percent during the first week of February 2016. The AfD is now Germany’s third-largest party, with 12 percent support.

Eighty-one percent of those polled believe the government hasn’t a grip on the refugee situation. Sixty-three percent want a limit on refugees entering Germany. Of some relief for Merkel is that the overwhelming majority of Germans (94 percent) say it is right that Germany accepts people feeling war.

With Putin helping continue the war in Syria, the time Merkel needed back in December seems increasingly elusive. More than ever she needs a respite as voters prepare to give their verdict on her leadership in three important regional elections in March. That respite will not come from Putin.

- Here Is The Exchange That Left A Stunned Janet Yellen Looking Like A Deer In Headlights

For nearly one year, Wisconsin Rep. Sean Duffy has been Janet Yellen’s nemesis over the ongoing probe into Fed leakage of material inside information via Medley Global and any other undisclosed channels, one which has seen subpoeans be lobbed at the Fed which has been doing everything in its power to stall said probe, and which cost Pedro da Costa his job when he dared to ask questions at a Fed presser that were not precleared by his WSJ “Fed mouthpiece” peers.

Today, during Yellen’s appearance before the House Financial Services committee, Duffy finally had enough, and in a heated exchange asked Yellen what on legal authority is the Fed exerting privilege to ignore a Congressional probe into what is clearly a criminal leak, one which has nothing to do with monetary policy and everything to do with the Fed providing material, market moving information to its favorite media and financial outlets.

The exchange highlights are below:

DUFFY: We sent a letter in the Medley investigation, in our oversight of the Fed, asking you for information regarding communication. No compliance. Then we sent you a subpoena in May, you did not comply with that.

We had partial compliance in October. We’re now a year after my initial letter. I’ve asked you for excerpts of the FOMC transcripts in regard to the discussion — in regard to the internal investigation on Medley. You have not provided those to me. Is it your intent today to promise that I will have those, if not this afternoon, tomorrow?

YELLEN: Well, congressman, I discussed this matter with Chairman Hensarling and indicated we have some concern about providing these transcripts… given their importance in monetary policy.

DUFFY: So let me just…

YELLEN: And I received a note back from Chairman Hensarling last night, quite late, indicating your response to that. And we will consider it and get back to you as soon as we can.

DUFFY: Oh no, no. I don’t want you to consider it and I think the chairman would agree with me, that this is a conversation, not about monetary policy. This is not market-moving stuff. This is about the investigation and the conversation of a leak inside of your organization. So this institution is entitled to those documents, wouldn’t you agree?

YELLEN: I will get back to you with the formal answer.

DUFFY: No, no, listen.

YELLEN: I believe that we have provided you with all the relevant information.

DUFFY: That’s not my question for you Chair Yellen. If I’m not entitled to it, can you give me the privilege that you’re going exert that’s going to let me know why I’m not entitled to those documents?

YELLEN: I said we received well after the close of business yesterday a letter explaining your reasoning and I will need some time to discuss this matter with my staff.

DUFFY: I don’t want — listen. I sent you a letter a year ago on February 5th. I had to send you a subpoena. You knew that I’m looking for these documents, you knew I was going to ask you about this today. So if you’re not going to give me the documents, exert your privilege, tell me your legal authority, why you’re not going to provide this to us.

And while a video of the exchange can be watched below (we will substitute a higher quality version when we can find one)…

The end result was this:

… which after just one more push by a few good men in authority, will be the same as another picture very familiar to regular Zero Hedge readers.

We just wonder if there are still a “few good men” left, daring to challenge the head of the Fed on what any other mere mortal would have been in prison for, long ago.

As for the “deer in headlights” look, and why Yellen is so adamantly refusing to comply with subpoenas and provide the US population and Rep. Duffy with the requested information regarding how it was that the Fed leaked critical information to Medley Global’s (founded by Richard Medley, former chief political strategist to George Soros) Regina Schleiger, the answer as Yellen explained last May…

… is simple: Yellen herself was the source, only there is no definitive proof… yet, as confirmation that the Chairwoman herself leaked the information in question would be grounds for prison time.

And since we doubt that Janet would chose a legacy of being the first Fed Chairman thrown in jail, even if it is not that far below a legacy of totally mangling the Fed’s attempt at renormalizing rates at a time when the entire world was careening into a recession, we expect absolutely no cooperation by the Fed in this ongoing criminal matter.

- Why Ron Paul Is Hopeful

Submitted by Ron Paul via The Mises Institute,

[This article appears in the January-February 2016 issue of The Austrian.]

I think the most exciting message for me today is that things are changing.

Often, when I come to these events, people ask me, “isn’t this grueling, isn’t this very tough?” It’s not, though, and it’s actually a little bit selfish on my part, because I get energized when I meet all the young people here. It’s true there is a spread of ages here, but there are a lot of young people and some of them even come up to me and say “you introduced me to these ideas when I was in high school a few years ago.”

And it’s not just people at events like these. When I landed at the airport on my way here, I was approached by two young people who came up to talk to me. They didn’t know each other, but both spoke with foreign accents, and both said they were from Africa. They said they heard the message of liberty over the Internet, and they had been following me ever since 2008.

Positive Trends

These are just examples, but I do think they represent a larger change that is taking place right now. Things are changing dramatically and in a favorable way.

We’re in this transition period right now where the attitudes are changing. But our views have been out there a long time, so we have to ask ourselves why we’re seeing more success now among the young and many future leaders.

Part of this is just due to greater availability of ideas. The Internet certainly helps, and a lot of the credit must go to organizations like the Mises Institute that make the ideas of liberty more easily available to everyone.

I also never imagined that my presidential campaigns would get the attention they did for our ideas. Our success in bringing new young people into the movement surpassed anything I thought was possible.

Change Will Come Whether We Like It or Not

But the reason we see more success for these ideas is not just because it’s easier to find them and read them. We’re living in a time when people — especially young people — can see that the old ideas aren’t working any more.

The young generation has inherited a mess from the older generations, and the young can see that what they’ve been told isn’t true. It’s not true that you can just go to college, run up a bunch of student debt, and then get a good job. The young can see that the middle class is being destroyed by our current economic system. And they can see that our foreign policy is failing.

Whether we like it or not, change will come. The troops will come home. They probably won’t come home for ideological reasons, but simply because the United States is broke and can’t afford all its wars anymore.

We’re also living in a time when the economic system is going to come unglued. The old Keynesian economic system isn’t working and young people can see it.

If it is true that we’re in the midst of an end of an era, though, the question remains as to what’s going to replace the system we have now. There are still plenty of socialists — popular ones — who are out there saying that what we need is more government control and more war to fix the economy and the world. So, we still have a lot of work to do, but I think we’re in a better place now than we’ve been in a long time.

We Don’t Need a Majority

When thinking about all the work we still have to do, it’s important to keep in mind that we don’t need majority support. If you’re waiting for 51 percent of the population to say “I’m libertarian and I believe everything you say,” you’ll lose your mind. What we need for success is intellectual leadership in a country that can influence government and the society overall.

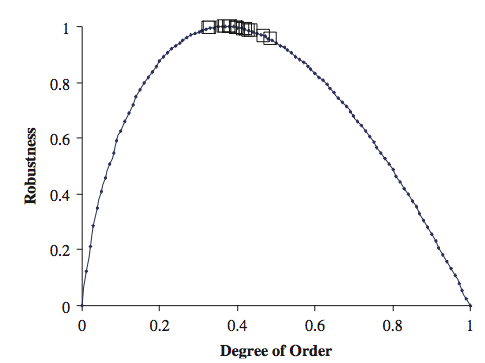

That’s where the progress is being made. We’re only talking about 7 or 8 percent of a country that is necessary to provide the kind of influence you need. This was the case during the American Revolution, and it’s true today. You are part of that 8 percent.

When doing this work, though, there are many things that can be done. People often ask me “what do you want me to do.” My answer is: “do what you want to do.”

There is no one way. Some people can use the political system, and others can go into pure education. Lew Rockwell started the Mises Institute, but what you do for the cause of liberty is personal to you, and you have to find what makes sense for you.

Also, you can’t know all the positive effects your work is having. I certainly had no way of knowing all these years how I was having an effect on those young Africans I met at the airport. You can’t always know what effect you’re having either.

Where To Start

So, say that we are successful, and our 7 or 8 percent continues to gain influence. What should we be doing? I think there are three basic places we need to start.

First off, we would see to it that there would be no income tax in the United States ever again.

Second, we would take the Federal Reserve and all its leadership and relegate them to the pages of history.

We would then pass a law that the US government cannot commit any crime that it punished other people for. It’s wrong to steal and hand people’s property over to other people, no matter how much people who do that win the applause of others.

And finally, we would bring all the troops home. Randolph Bourne was right when he said that war is the health of the state. Peace is the friend of liberty and prosperity.

We Need Humility

As a final note, I’d like to say that humility and tolerance need to be an important part of our efforts.

Yes, we need a foreign policy based on humility. We can’t know what’s right for people around the world, and we certainly shouldn’t force anything on them.

But right here at home, we need humility also. In fact, libertarianism is based on humility. We can’t know what’s best for other people. No one can, and that is why we want people to have the freedom to do what they think is best for themselves.

This is true in economics, of course. Do you think Janet Yellen knows what the “correct” interest rate is? There are many things that economic planners can’t possibly know. And for that reason — and others — there are so many things they shouldn’t be doing.

And yes, there are a lot of people out there living their lives in ways we might disagree with. But intolerance is what government is based on. The far left, they are very intolerant and are happy to have people with guns tell other people how to live.

We need to keep in mind that if other people aren’t hurting us or using government to force their way of life on us, they should be left alone.

Unlike the left, we want tolerance for other people’s morals and for how other people work for a living and what they choose to do with their money.

We need more tolerance and humility in every aspect of life, and that’s how we get a free society.

So, let’s all go to work and preserve the cause of liberty.

- Why Trump Thinks Unemployment Is 42%

During his victory speech last night in the New Hampshire Republican primary, Donald Trump exposed what everyone knows but doesnit dare admit: the "phony" unemployment numbers that Obama continues to crow about and The Fed is so focused on….

"Don't believe those phony numbers when you hear 4.9 and 5% unemployment. The number's probably 28%, 29%, as high as 35%, in fact, I even heard recently 42%,"

How does he justify such large estimates? Simple…

"If we had 5% unemployment, do you think we'd have these gatherings?"

Tough to argue with that – just as Hillary and Jeb…

- "It's Probably Something" – Gold Surges Above $1200; USDJPY, Oil, Stocks Plunge

With US markets failing to hold on to today's "Deutsche Bank" euphoric gains today despite, or rather due to Janet Yellen's Congressional testimony, traders in mainland China remains locked out due to the Lunar New Year holiday, while Japan is mercifully taking a break – mercifully, because otherwise the Nikkei would be crashing. However, one market is back online as Hong Kong traders return to their desks to see carnage around the globe, and most importantly, are unable to hedge arbed exposure between China, Japan and the US.

So, with few options, they are buying the one asset that provides the best cover to central banks losing faith, demonstrated most vividly by the total failure of the BOJ, and as a result just as Yen soars above 113… with USDJPY down a stunning 10 handles from the post-NIRP highs…

.. and Gold has taken out the numerous $1,200 stops…

and is currently surging to levels seen at the end of QE3…

What is causing this mad rush into gold is unclear, but… it's probably something.

Meanwhile, as gold is soaring, its BOJ pair trade equivalent (as described in An Inside Look At The Shocking Role Of Gold In The "New Normal") the USDJPY, just tumbled below 113 for the first time since 2014, and with no support levels until 110, this may just be the final straw not only for Kuroda but for the entire Abenomics house of hollow cards.

In any case, don't expect the gold surge to last too long: our good friend, Benoit Gilson, manning the Bank of International Settlements' gold and FX desk, will be on alert very shortly.

Away from currencies, WTI is also collapsing, to a $26 handle…

Asian equity markets are crashing…

- *HANG SENG CHINA ENTERPRISES FUTURES TUMBLE 6.3% AT OPEN

- *HONG KONG'S HANG SENG INDEX FUTURES SINK 4.9% AT OPEN

With energy-related stocks crashing…

- *CNOOC SHARES FALL 7.5% TO HK$7.28 IN HONG KONG

- *SINOPEC SHARES FALL 8.7% TO HK$4.00 IN HONG KONG

- *PETROCHINA SHARES FALL 7% TO HK$4.38 IN HONG KONG

- *CHINA OILFIELD SHARES FALL 4.1% TO HK$5.10 IN HONG KONG

And banks catching down…

- ICBC falls as much as 6.3% in Hong Kong to lowest intraday level since Oct. 2011.

- China Construction Bank drops as much as 5.4% to lowest intraday level since April 2009

- Agricultural Bank of China sheds as much as 5.9%, lowest intraday level since Oct. 2011

- Bank of China drops as much as 5.2%

And US equity futures are tumbling (Dow -125)…

Someone in Hong Kong is having a very bad day.

- Good News: Hookers Aren't Planning To Hike Rates

As regular readers are no doubt aware, we like to check in on the hookers from time to time.

By that we of course mean SouthBay Research’s Vice Index, which tracks spending on fun activities in the cash economy.

Fun activities like boozing, gambling, and escort hiring. “Luxury good spending is sensitive to shifts in the economic winds, vice is even more so,” Andrew Zatlin reminds us. “A prostitute costs almost two days of after-tax wages [and] the consumer’s stack of money has to be a certain height before they can get on that ride.”

That’s right. You don’t want to “get on that ride” if your funds are low and so, Zatlin likes to pitch the index as a leading indicator for consumer spending. Below, find his latest including an up to date reading on the Vice Index and the second annual Hookernomics Survey.

* * *

Submitted by SouthBay Research

Vice spending is coasting

Although the pace of Vice Spending appears to have surged starting mid-2014, that’s really a quirk of the 2013 comparables. In reality, spending has been growing at a steady, flat 2% pace. It corresponds to Retail Spending (ex auto & gas) y/y rate of 3.5%.

Hookernomics

Results from our 2nd annual Hookernomics Economic Survey

- The Good News: Inflation & income growth expectations remain subdued.

- The Bad News: Income growth expectations are subdued.

NOTE: This survey was conducted in early January. Any impact from a stock market collapse is probably not reflected.

The Hookernomics Survey follows the Federal Reserve Regional Bank Business Outlook Surveys. Business owners (escorts) are asked their opinions about current and 6 month business conditions. The questions focus on similar topics: Prices, Costs, New Orders, and Inventory.

Last year’s survey results: No inflation, continued steady-as-she-goes economy

Last year respondents reported that there was no change in demand or activity. Customer demand was the same, indicating no meaningful or anticipated change in incomes beyond normal raises.

This year, Same as Last Year: No inflation, continued steady-as-she-goes economy

Inflation still tame:

- Are your costs rising? Somewhat

- Do you expect prices to increase in the next 6 months? No

- Do you expect to raise prices in the next 6 months? No

Escorts raised prices in 2015, largely in response to several years of rising hotel costs. What began as tentative rate hikes turned into widely adopted increases.

Hotel inflation remains a sore spot.

Hotel prices continue to trickle up and apparently the Priceline bargains are less of a bargain than they used to be. So here comes AirBnB: many escorts have begun using it as a viable alternative.

However, having raised rates relatively recently, respondents reported no plans for a repeat.

Customer demand remains steady

- Has demand changed (number of clients, frequency of appointments, etc)? Do you expect demand to change? No increase or decrease in demand

- Is there a change to amount of money spent per transaction? No

This is a very price elastic market. The only reason price hikes held last year was that all escorts raised their prices; customers had little choice. But it’s also a testimony to income growth: customers had the available disposable income.

That trend continues this year: no deceleration in consumption points to continued expectations of job security.

But that’s also a problem: no extra spending suggests that customer don’t expect much in the way of higher disposable incomes. And that’s before the stock market collapse is taking hold.

Inventory remains steady

- Are you encountering any increase or decrease in competition? No

- Do you believe that the number of other escorts is the same, more or less? Same

There are essentially no barriers to entry. That means that in times of economic stress, more providers can easily enter the market.

Or, put differently, no changes in the volume of providers indicates no change in the economy.

That’s a big difference to early last year when many providers and adult film stars were travelling to boost business.

* * *

Of course all of this may not matter.

If central banks end up heeding the “ban cash” calls on the way to developing a government-sponsored digital currency that allows PhD economists to take away citizens’ econommic autonomy and institute deeply negative rates the cash economy may simply die out.

Unless the hookers start taking Visa, that is.

- "Fasten Your Seatbelts": Kyle Bass Previews The Collapse Of China's $34 Trillion Banking Sector

Earlier this month, Kyle Bass asked a funny question in a discussion with CNBC’s David Faber. To wit: “If some fund manager in Texas is saying that your currency is dramatically overvalued, you shouldn’t care on a $10 trillion economy with $34 trillion in your banks. I have, call it a billion – it’s so small it should be irrelevant and yet somehow it’s really relevant.”

Bass was referring to China’s penchant for firing off hilariously absurd “Op-Eds” in response to anyone who suggests that the country may indeed be experiencing the dreaded “hard landing” or that a much larger yuan devaluation is a virtual certainty. The People’s Daily literally laughed at George Soros when the aging billionaire said he was short Asian currencies in Davos. “Declaring war on China’s currency? Ha ha,” PD wrote. Chinese media also called Soros a “crocodile,” a “predator,” and said his yuan gambit “cannot possibly succeed.”

That’s what Bass means when he says the Chinese seem to be quite ornery for a country that claims to be unabashedly confident about the prospects for their economy. Bass, like Soros, is betting on a steep devaluation of the yuan. In fact, he thinks a one-way bet on RMB weakness is “the greatest investment opportunity right now.” The thesis is simple. Here’s some of our commentary from last week followed by key excerpts from the CNBC interview which should serve as a nice recap of why Bass thinks the yuan is set to fall by 30-40%:

China’s banking system, Bass told CNBC, is a $34 trillion ticking time bomb, and when it explodes, Beijing will need to plug the holes. $3.3 trillion in FX reserves will be woefully inadequate, he contends.

“Very few people have looked at what the cause of the problem is,” Bass begins. “They’ve let their banking system grow 1000% in 10 years. It’s now $34.5 trillion.”

Bass then goes on to note that special mention loans (which we’ve discussed on any number of occasions) are around 3% of total assets. “If they lose 3%, that’s a trillion dollars,” Bass exclaims. Ultimately, Bass’s argument is that when China is forced to rescue the banking system by expanding the PBoC’s balance sheet, the yuan will for all intents and purposes collapse. This is of course exacerbated by persistent capital flight.

Below, find some other soundbites from the interview. Notably, towards the end, Bass says that if China is right and speculation around a much larger devaluation is indeed unfounded, then it’s curious why China seems to care so much about what “one fund manager in Texas thinks.”

From Kyle Bass:

“The IMF says they need $2.7 trillion in FX reserves to operate the economy. They’ll hit that number in the next five months. Those who think they can burn it to zero and they have a few years ahead of them, they really only have a few months ahead of them.”

“When they lose money in their banks they’re going to have to recap their banks. They’ll have to expand the PBoC balance sheet by trillions and trillions of dollars.”

“No one’s focused on the banking system. Focus will swing to it this year.”

“A Chinese devaluation of 10% is a pipe dream. It will be 30-40% by the end.”

“If some fund manager in Texas is saying that your currency is dramatically overvalued, you shouldn’t care on a $10 trillion economy with $34 trillion in your banks. I have, call it a billion – it’s so small it should be irrelevant and yet somehow it’s really relevant.”

“If 4% of the population takes out their $50,000 quota, the FX reserves are gone. We lose ourselves in the numbers. $3.3 trillion is a big number, but the reserves to bank assets number is one of the worst in the world.”

On Wednesday, Hayman is out with a 12-page letter to investors in which Bass explains why he’s making such an outsized bet against China. Most of what Bass says has been covered in these pages extensively for years.

Put simply: China has an enormous debt problem and the rapidly decelerating economy means that the country’s banks will only be able to paper over the soaring NPLs for so long. If Beijing wants to eliminate the acute overcapacity problem that’s contributed mightily to the global deflationary supply glut, it will mean allowing the market to purge misallocated capital. And that means bankruptcies and a wave of defaults. “The unwavering faith that the Chinese will somehow be able to successfully avoid anything more severe than a moderate economic slowdown by continuing to rely on the perpetual expansion of credit reminds us of the belief in 2006 that US home prices would never decline,” Bass begins.

“Banking system losses – which could exceed 400% of the US banking losses incurred during the subprime crisis – are starting to accelerate,” Bass adds. “Our research suggests that China does not have the financial arsenal to continue on without restructuring many of its banks and undergoing a large devaluation of its currency.”

He goes on to recap the entire thesis, including the idea that WMPs are a big, big problem (something we’ve said on dozens of occasions including here when we called WMPs an “8 trillion black swan”) and you can read the full letter below, but excerpted is the “what happens next” portion, in which Bass explains how things are likely to play out in the not-so-distant future for the engine of global growth and trade.

* * *

From Hayman Capital

What Happens Next? – Fasten Your Seatbelts

The troubles in China are much larger than market participants believe. Everyone (including Chinese citizens) knows something is wrong, but few, if any, can put their finger on exactly what it is. The narrative to date has been focused on the symptoms of the problem (i.e. capital outflows and low commodity prices) as opposed to the problem itself. We believe the epicenter of the problem is the Chinese banking system and its coming losses. Once analysts, politicians, and investors alike realize the sheer size of the impending losses and how they compare to the current levels of reserves, all focus will swing to the banking system.

As it is obvious that China’s economy is slowing and loan losses are mounting, the primary question is what are China’s policy options to fix the current situation? We believe that a spike in unemployment, accelerated banking losses / a credit contraction, an old-fashioned bank run, or more likely the fear of one or all of these events, will force Chinese authorities to act decisively. The policy options that China has then are limited to:

1. Cut interest rates to zero and let the banks “extend and pretend” bad loans – lower interest rates will force more capital abroad putting downward pressure on reserves and the currency.

2. Use reserves to recapitalize its banks – this will reset the banking sector, but wipe out the limited reserve cushion that China has built up, and put downward pressure on the currency.

3. Print money to recapitalize its banks – this will reset the banking sector, but the expansion of the PBOC’s balance sheet will lead to downward pressure of the exchange rate.

4. Fiscal stimulus to revive the economy – this will help some chosen sectors of the real economy, but at the expense of higher domestic interest rates (if not done in conjunction with Chinese QE). The 2009 fiscal stimulus was primarily executed through the banking sector so a similar program would require a properly capitalized banking sector. Also, any increase in Chinese investment would reduce China’s trade surplus and ultimately pressure the currency.

The playbook from policy makers to deal with China’s challenges will likely combine several of the above measures, but ultimately a large devaluation will be a centerpiece of the response. This will allow the Chinese economy to regain the competitiveness it has lost over the past few years.

Chinese officials will realize that a meaningful devaluation is exactly what China needs to help rectify the imbalances that have built over time. Look to Japan, Russia, Brazil, Mexico, and Europe as examples of countries (or a monetary union in the case of Europe) that have allowed their currencies to depreciate in order to correct the imbalances in their economies. This begs the question of whether governments are going to engage in a full-on currency war. In our view, this has already begun. One only has to look at what BOJ Governor Kuroda said to the Chinese during a panel at Davos last month. He told them to impose stricter capital controls to stem the flow of hot money out of China and to stabilize their currency. Just one week later, he moved the BOJ to negative rates and devalued the yen 2% versus the renminbi overnight. There is one thing central bankers loathe, and it happens to be free advice.

Once China realizes that it must save its banks (China only has a newly established deposit insurance system with limited coverage and little pre-funding, which could make bank runs very problematic), it will do so. The Chinese government has the capacity and the willingness to do what it needs to do to prevent a banking system collapse. China will save its banks, and the renminbi will be the valve for normalization. It is what any and every government would do if put into a similar situation.China should stop listening to Kuroda, Lagarde, Stiglitz, and Lew and start thinking about how to save itself from the impending disaster in its banking system.

Remember, Bernanke had the subprime crisis wrong when he said it was “contained,” Lagarde and Sarkozy had it completely wrong when they said speculators were the cause of Greece’s problems, and now they all have it wrong when they say China’s problems are due to a simple “communication problem” regarding its FX policy. The problems China faces have no precedent. They are so large that it will take every ounce of commitment by the Chinese government to rectify the imbalances. Risk assets will not be the place to be while all of this is happening.

Once we drew this conclusion in the middle of last year, we decided to liquidate the majority of our risk assets and position ourselves for the various events that are likely to transpire along this long road to a Chinese credit and currency reset. The next 18 months will be fraught with false-starts, risk rallies, and second-guessing. Until China experiences a significant devaluation, it will not be able to cope with the build-up of credit that has helped fuel its rise, but may, in the short-term, be its undoing.

- "Negative Rates Are Dangerous" OECD Chair Warns "Our Entire System Is Unstable"

Submitted by Erico Matias Tavares via Sinclair & Co.,

William R. White is the chairman of the Economic and Development Review Committee at the OECD in Paris. Prior to that, Dr. White held a number of senior positions with the Bank for International Settlements (“BIS”), including Head of the Monetary and Economic Department, where he had overall responsibility for the department's output of research, data and information services, and was a member of the Executive Committee which manages the BIS. He retired from the BIS on 30 June 2008.

Dr. White began his professional career at the Bank of England, where he was an economist from 1969 to 1972. Subsequently he spent 22 years with the Bank of Canada. In addition to his many publications, he speaks regularly to a wide range of audiences on topics related to monetary and financial stability.

In the following interview he shares his views in a totally personal capacity on the current state of the global economy and related monetary and fiscal policies.

E. Tavares: Dr. White, we are delighted to be speaking with you today. You are recognized as one of the leading central bank economists in the world, and so your perspective is highly valued and appreciated.

Absent the robust central bank intervention in 2008 the world’s financial system would have likely collapsed. However, in a sense the economy looks riskier now: government debt levels as a function of GDP are at record highs; big financial institutions have gotten even bigger; and while we may not have a housing credit crisis brewing in the US, we are seeing stress in many areas, from student loans to energy bank loans to emerging market convulsions. At the same time, income inequality has blown out of proportion as booming asset prices hardly benefited the less privileged in society.

With the benefit of hindsight, can we say that the very loose monetary policy of central banks around the world lulled politicians and investors into a false sense of security and that those unresolved issues from the recent past could still come back to haunt them? Or can they keep things under control with these newly found monetary “bazookas”?

W. White: I think your assessment of where we are at is spot on. What the central banks did in 2008 was totally appropriate. The markets were basically collapsing. We had a kind of a “Minsky moment” problem with market illiquidity and the central banks did what they had to do.

Since then the focus has changed. I believe that it was in 2010 when Ben Bernanke, then Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, made clear in a speech that the objective of monetary policy – and specifically quantitative easing – was basically to stimulate aggregate demand. And since then we have had all the central banks around the world pursuing that objective through increasingly unconventional measures.

However, there is a fundamental shortcoming in using monetary policy in this way. Just as you described it, the fundamental problem we all face is a problem of too much debt, you know, the headwinds of debt. In a sense it is a problem of insolvency. And relying on central banks to correct this is totally inappropriate, because they can handle problems of illiquidity but they can’t handle problems of insolvency. So I think that the fundamental orientation here is wrong.

Now, why is this happening? In part, I think, it’s because dealing with problems of insolvency, debt reduction, making debt service more bearable and so forth, demands policies that only governments can implement. Moreover, these policies are likely to be technically hard to implement and will also meet stiff political resistance. You know there’s this old line from Daniel Kahneman: we have to believe – we are hardwired to believe – and so since we must believe then it’s just as well to believe in something convenient. And I think the politicians find it convenient to believe that the central banks have it all under control.

But it’s not true, because what we have been doing is both losing efficacy over time, that is to say that the efficiency of the transmission mechanism seems to me to be getting less and less, while the impact of the associated unintended consequences, the side effects of monetary policy, are becoming more and more evident. In the end this is really going to cause us problems.

And of all the unintended consequences I could list, lulling the governments into a false sense of security is probably the most important.

ET: In a modern financial economy, liquidity is created primarily by the banks through credit creation. When that liquidity creation slows down typically the economy falters. So as the banks were forced to deal with credit and balance sheet issues from 2008 onwards, the central banks stepped into that role by cheapening the cost of credit and conducting large scale asset purchases to make sure that liquidity continued to flow throughout the economy.

However, even that seems insufficient to rekindle economic growth, prompting some central banks to go a step further and adopt negative interest rates (“NIRP”). Japan is the latest convert. Is that the likely next step for other central banks, including the Fed?

WW: I think it is entirely possible. But before I get into that I would like to comment first on the efficacy of monetary policy as you briefly outlined. The whole thing is premised firstly on the idea that easy money will stimulate demand, and secondly that the unintended consequences are nothing to worry about.

On that first issue, I have very serious doubts whether the very easy money policies will have the impact that central bankers believe it should have. And after seven years of the slowest recovery ever, it seems to me that there is empirical support for that proposition.

Now why do I think it won’t work? I think what they’ve done, particularly the unconventional stuff – and there has been so much of it, including forward guidance, quantitative easing, qualitative easing and now NIRP – has led many people into looking upon all of this as experimental policies smacking of panic. And, as a result of the associated uncertainty, they may have hunkered down instead of going out and spending the money.

There’s another point which is closely related. Think about interest rates being brought down to very low levels. The whole point is trying to attract spending from the future into today, what is known as intertemporal reallocation. That is just fine. But if you’re bringing that spending forward, at a certain point when tomorrow becomes today – as indeed it must inevitably do – then that future spending that you might otherwise have done is constrained by the spending that you have already done. And that manifests itself in increasing debt levels, which indeed we have already seen.

So, almost by definition, monetary policy only works for a relatively short period of time. We have had six or seven years of it at this point and I think that’s hardly a short period. There are all sorts of other issues that I won’t go into now, but that’s where we are.

ET: If we have reached that exhaustion level, then the next step is NIRP right? Is that the natural progression given the “panic mindset” that you alluded to?

WW: You used exactly the right word, it is a mindset. They believe that they understand how the economy works and they are going to do more of what they consider to be a good thing. And we’ve seen this process at work over the course of the years. I remind you that, when the Fed started this ultra-easy stuff, the Europeans were very hesitant to go into it. But, in the end, Mario Draghi and the ECB have gone into it with both feet and are proceeding along the broad lines of what the Americans initiated.

The thing that strikes me about NIRP is the possible analogy between the zero lower bound and quantum mechanics. The Newtonian laws of motion apply as long as the body in motion is not too small and is not going too fast, otherwise you need to make use of quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity. And maybe with monetary policy there is a similar kind of a phase change that occurs at the zero lower bound.

The Europeans were concerned about this, based on earlier Danish experience when the central bank started charging negative rates on excess reserves held by the banks at the central bank. The expectation is that this will lead to lower lending rates. But you can easily think of a story where this is not the outcome because those negative interest rates cut the banks’ profit margins. And then the question is what will the banks do to restore them?

Well, one thing they could do is lower the deposit rate. I read in the Financial Times a few days ago that Julius Baer in Switzerland is thinking about doing just that. But then the worry is that people will take their money elsewhere, take it out in cash or whatever. If this is not possible, then what is possible is increasing the lending rate. What you end up with is a counterintuitive but highly plausible alternative description of what these policies are going to give you. So in the end they may end up being contractionary and not expansionary.

So totally experimental in any event.

ET: Actually we do have some empirical evidence after some central banks adopted NIRP, such as Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark. As interest rates fell, people saved more, which is the opposite of the policy objective. It seems that because people, particularly the older folks, earn less interest they have to save more to meet their needs.

WW: Absolutely. But I would associate that argument more with the general question of whether additional quantitative easing will produce the desired increase in aggregate demand. The NIRP is sort of an extension of that kind of argument.

There are lots of reasons why lower interest rates might produce lower consumption. For example, think about the people who are saving for an annuity or a pension for when they retire. If the roll-up rate is going down, aside from working longer, the only solution is to save more. You need a higher base, given that lower roll-up rate, to achieve a particular target level of wealth to buy an annuity of the desired size at the point in time when you want to retire.

There are all these distributional issues to consider too. You know, all these policies have buoyed asset prices a lot and richer people – the ones who have the financial assets and the big houses whose values have increased the most – have gained the most. Conversely, middle class people whose financial assets are largely in the banks, have lost out. Since richer people tend to have a lower marginal propensity to consume out of both income and wealth, then these redistribution effects could cause the economy to grow more slowly, not more rapidly.

Andrew Smithers of the Financial Times has offered a compelling explanation as to why business investment has also been so weak in spite of monetary conditions being so easy. It relates to the unexpected interaction between lower interest rates and corporate compensation schemes. When interest rates go down it becomes cheaper to borrow money, which can then be used to buy shares thus pushing up equity prices and the value of the associated option compensation schemes.

So from the perspective of the senior management – and for that matter, the “sharp” holders of equities who know that the shares are overvalued – it makes a lot of sense to buy back shares because they are personally making a lot of money out of it. But in the process they are also hollowing out the corporation because they are cutting investment to hoard cash for the same reason. And the “dumb” holders who did not sell the shares in the buyback are left holding the bag. That shell of a corporation is not going to be able to produce the returns in the future the way it did in the past. And this is an unexpected consequence of the interaction between easy money and corporate compensation schemes.

As you can see there are many reasons why lowering interest rates – and in the limit NIRP – could lead to less spending and not more. Having said that, I did notice from reading the newspapers how this thing is spreading out. Haruhiko Kuroda, the Governor of the Bank of Japan, until recently maintained that there was absolutely no way he would ever do NIRP, not even thinking about it. Then he went to Davos a couple of weeks ago, came back and did it.

Insofar as the Americans are concerned, who are now outliers for not having negative rates, we had Ben Bernanke just two weeks ago saying the Fed should think about it. Alan Blinder apparently said it’s a good idea, and Janet Yellen, who previously said it is too dangerous, now says that the Fed should consider it. So here we have that mindset again.

ET: It’s creeping in. You bring up a number of important counter-arguments that should be considered in policy making, which gives us some hope in our economics profession. And yet it seems the default is always more of the same, with the consequences we have been discussing.

Let’s pick up on the issue of solvency you brought up earlier, which could also be frustrating the outcomes of central bank policies. We can use Portugal as a case study in this regard. Until recently it was under the direct economic supervision of major international financial institutions and all the brainpower that comes with it. The previous government, replaced only a few months ago, had been praised for implementing a very strict austerity program.

And yet, the economy pretty much stagnated, unemployment remained high and government debt levels as a function of GDP exploded – to the point where nominal growth for the most part does not cover government interest payments. The banking sector in turn remains in a dicey situation, with several high profile bankruptcies just in the past months. While central banks are critical in providing liquidity, how can a country like Portugal become solvent again?

WW: Here you have one of those unintended consequences I alluded to before. It turns out that these ultra-easy monetary policies induce people to take on more debt. In the longer run it’s those debt problems that become a headwind, and if that headwind is of such a magnitude that it affects the solvency of the banking system as well, then we have a real problem.

There is now a huge literature on this. You are familiar with Ken Rogoff’s and Carmen Reinhardt’s book on financial follies over the ages which, along with pieces by Jorda, Taylor and Schularick and others, describe the dynamics at work here. When you get a combination of an economy which is hurting because of debt problems, where the corporate and/or the household sectors are facing these big headwinds of debt, and in addition the banking system becomes challenged, with non-performing loans and the like, the resulting periods of unusually low growth can go on for a decade or more. Carmen and Vincent Reinhardt also did a big paper at Jackson Hole on this in 2010 where I was the commentator. If you get a joint problem of this nature associated with too much debt both in and out of the financial system you have a tiger by the tail.

Now specifically on Portugal, the McKinsey Global Institute recently published a paper on debt and deleveraging all over the world. Out of the six countries which had the biggest increase in sovereign debt to GDP ratios since 2007, four of them were in peripheral Europe, including Portugal. I have followed the Greek situation a little more closely and I know for a fact that in their case they have implemented actual fiscal measures that took out 18% of GDP out of the economy. In spite of this, and the fact that the private sector took a big haircut, the overall debt to GDP has risen to above 200% of GDP as GDP has sunk like a stone.

ET: So, clearly, some of what has been done has made things worse, not better. The question is what are the alternative policies when you are dealing with a solvency problem of this nature? And related to that, how to make debt service more manageable?

WW: The first thing I would say is to have less austerity and more pro-growth spending. Now I qualify each of these things with the recognition that sometimes and in some countries this will not be possible because of confidence effects in market. Nevertheless, European experience does point to the merits of less austerity as opposed to more. I particularly think that there are many countries, maybe Portugal is part of this, where there should be a lot more government money spent on infrastructure: the US, Germany, Canada, and the UK would certainly be included. There are needs for more infrastructure in many countries, and with the interest rates being so low, I really don’t understand what the hang up is.

I also think that there are a number of countries following essentially mercantilist policies and it would be much better if they re-orientated themselves domestically so that wages could get a larger share of incomes. In countries like Germany, China, Japan, South Korea, for a long period of time and still continuing, that sort of mercantilist approach basically said that you have to keep wages down. I think that has not been helpful, and that we could do more to encourage wage income and spending in many countries.

We also need many more write-offs – not just debt restructuring but actual reduction of the principal. Willem Buiter has written a lot on this, in terms of replacing debt with equity, so that the risks are more evenly shared. And lastly, we need more structural reforms. At the OECD, they believe that there’s still a lot of low hanging fruit out there, in terms of freeing up labor markets, product markets and so forth.

The answer to insolvency is not simply to print more money – it may get you out of the problem in the short-run but it simply makes it worse and worse over time. At some point, maybe where we are now, you truly get to the end of a line. You see that what you have been doing is just a short term palliative that is actually making the disease worse.

ET: We wrote about Greece a year ago and pointed out that the economic transformation being asked in connection with the new bailout was akin to converting a proverbial “couch potato” into an Olympic athlete almost overnight. Given how poorly they rank across a number of competitiveness statistics after being in the European Union for decades now, at best this is something that will take many more decades to turn around. It really makes you wonder what kind of shock therapy is needed to rehabilitate that economy.

There’s one other policy that while a political taboo might also be considered: leaving the Euro. Greece has tried the alternative, which is austerity – internal devaluation by another name – with very poor results. So why not give this one a go?

WW: This raises an important question. Suppose Greece exits and depreciates its new currency to stimulate exports and economic growth. Will depreciation prove successful?

In addressing this question, we get back to some fundamental structural issues. There is in fact a developing literature on this topic at the moment. In part, this literature is a response to the puzzle that both the Japanese Yen and Sterling depreciated a lot recently yet nothing seemed to have happened in terms of the external side.

I think there are a lot of grounds to believe that depreciation works less well than it used to. First, in Greece we know that wages have come down a lot. But the country is characterized by such a degree of oligopoly and rent-seeking that all that’s happened is that profit margins have gone up. As a result, there’s no signal coming through prices to get a change in resource allocation from non-tradables to tradables.

Second, you have all sorts of institutional barriers to entry and to exit of old unproductive firms – in Greece it takes almost four years for your average bankruptcy proceeding. If you have all these institutional impediments to the resources actually moving from the non-tradables to the tradables this is an excellent reason why depreciation might not produce the results intended.

Thirdly, it might not work because, in the end, all that will happen is that inflation will go up and any real benefits you may have gotten in the first instance just get eaten away.

Now, we should be thinking about all these alternatives in a serious way. They are very important issues. But you should not just immediately assume that a depreciation is going to be output expanding, particularly via an improvement in the current account.

Another thing that concerns me a great deal, and we can see this in spades inside the Eurozone, is that the portfolio elements and revaluations associated with depreciation are potentially much more important than trade effects. How are these people going to pay all these external debts which are denominated in Euros when they are earning revenues in a new but depreciated currency? To say nothing about the legal problems, there would be lawsuits left and right.

George Soros made the point, in the Financial Times a while back, with an article titled “Germany Should Lead or Leave”. His view is that you could avoid a lot of problems if the Germans left, not the Greeks. When currency unions split up in the past, normally it was the creditors who left. They see the writing on the wall and they are out of it. If anyone leaves it should be the Germans, the Dutch or whoever wants to go along with them. The debtors would keep the euro, minimizing legal battles, and the creditors would have to be cooperative to minimize their losses. That’s what Soros thinks.

The problems associated with leaving would be very great, so you would want to think very carefully about it. What are the benefits and what are the costs? Barry Eichengreen talked about this a few years ago in an article for Project Syndicate. He felt that an exit would precipitate the “mother” of all crises. And the other problem is you would have to do all your thinking in secret because the minute the people get a whiff of what was going on you would see the “mother” of all capital outflows.

ET: What is your view on using actual cash – notes and bills – as a monetary tool to stimulate the economy? It seems to us that having a stimulus instrument that does not add to the debt burdens of countries has some appeal. And it goes straight to the real economy, bypassing bank managers who may be reluctant to lend that money out. Aren’t the Swiss voting on a similar scheme in fact?

WW: I had an exchange of views in Project Syndicate with Adair Turner on this. Essentially what it comes down to is the question of helicopter money: the government spends the money and the central bank prints it. The particular variation here is you’re saying the government doesn’t actually spend the money; they just print the notes and give them to the ordinary citizens who will spend the notes.

Well, a number of points can be made about this. If you give people notes, and you’re putting more notes into the economy than they want to hold, the first thing they’ll do is take the notes and deposit them in the banks again. So it really doesn’t make any difference whether a central bank pays for a deficit with notes or through a cheque that is deposited and shows up as increased reserves held by banks at the central bank.

ET: True. They could also use them to reduce their debt loads…

WW: Right, I was coming on to that. My first point is that there’s nothing magical about notes. People hold as many of them as they want and the rest they put in the bank.

Now, I will contradict myself by saying that if the actual printing of notes was taken as a sign of the extraordinary problems being faced by the government, you could end up in a Zimbabwe-type scenario. And that could lead to hyperinflation almost immediately.

OK, having said that, if you give people notes or a government cheque, what will they do with the money? They might spend it or, as you have just said, they might actually save it. The latter is more likely in a high debt environment. Whether it’s high existing levels of household sector debt, or whether it’s a Ricardian equivalence where they see-through the government and realize that government debt is really their debt and higher taxes down the line. So they might just sit on it and not spend it.

In fact when you think about it, remember the old multiplier debate? Tax cut multiplier versus expenditure increase multiplier, which is greater? It was commonly said that the expenditure multiplier was larger because, when the government spent the money, it was buying goods and services with money that ended up in people’s pockets, which they could then spend again. But the problem with the tax cuts is that we’re back to what we just described. Getting a bank note or a check from the government is almost identical to a tax cut, the benefits of which you may or may not spend.

The question is always what will the people do with the money? And I think the answer could be nothing. So this is a less useful way to approach the problem. If there is something to be said about government expansion – I stress the word “if” – there is less to be said about doing it through notes.

Another thing worth mentioning is the suggestion that that the reserves held in the central bank are not debt. They are not liabilities of government. I think that’s just totally wrong. The central bank is 100% a creature of the government. So if you put the two balance sheets together and net them all out, whether it’s cash issued by the central banks, or whether it’s bank reserves on the liability side of the governments accounts, it’s all government debt.

Well, then you might then say that there is no problem with this kind of debt because it is debt that doesn’t pay any interest. But what if there are so many reserves in the system that the central bank has to take them out at some point? And here the government really only has two choices: either the central bank sells assets, which are then interest bearing assets held by the private sector, or it pays interest rates on the reserves, in order to increase the demand for reserves commensurate with increased supply. So you end up in a world where you are paying interest on that debt.

I think back to that article written by Sargent and Wallace in 1981 titled “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic”. There’s also a book written by Peter Bernholz about monetary and political regimes and inflation. Both of those pieces, the first the theory and the second the historical facts, suggest that if a government is running a big deficit and it’s already got a big debt, it has a big problem. And the problem is that the government has to borrow because the deficit is so great and the employees need to get paid. However, nobody will lend them the money because the stock of debt outstanding is too high. And the only answer is to go back to the central bank.

Peter has a magic number. If 40% of all of the expenditures of the government are being financed by the central bank, the historical record indicates that hyperinflation is significantly more likely. And what is really interesting at the moment in terms of magic numbers, for what all magic numbers are worth, is that the asset buying program at the Bank of Japan is now equivalent to financing 40% of government expenditures. We’re talking big numbers here.

I don’t think you need rational expectations, just people seeing the writing on the wall. Everything is fine until inflationary pressures or something else shocks up the interest rates. And the minute they go up, it becomes obvious that government debt service has gone high enough so they will have no recourse but to have the central bank finance still more. And when that happens the writing is on the wall, the currency collapses and the inflation becomes essentially uncontrollable. This is a highly non-linear process that cannot be captured by the econometric models that are in widespread use. They are essentially linear.

People say that all this stuff is innocuous, that “helicopter money” is a magic bullet to get us out of a debt problem. My own personal view – and I have to say that I hope I’m wrong – is that it is a highly risky and perhaps even terminally risky policy for countries that already have bad fiscal conditions. We should be thinking about the downsides.

ET: If high inflation rears its ugly head again, do you think central banks won’t be able to fight it? For instance, given the high debt load the US government has taken in recent years massively raising interest rates to curb inflation could create some serious fiscal problems going forward.

WW: I think it’s exactly so and it goes back to what we were just talking about. Suppose a country has a big debt, a big deficit, and a short maturity of debt and they raise interest rates. It’s entirely possible that this process of fiscal dominance not only begins but could be perceived to be beginning on the part of thoughtful investors. Then it turns into a flight to get out, and the flight then generates a dynamic which is self-fulfilling.

If you ask me who I am worried about today, I guess Venezuela is on top of the list, albeit a bit of an outlier. Brazil is a country that I think is very worrisome, with high interest rates, a bad fiscal position and short maturities.

The OECD over the course of the years has pointed out that Japan, the US and the UK are the countries that could have the most serious problems in this regard. However, the odd thing is that the OECD has been saying this for ages and yet everything in those three countries now has continued to be just fine. Conversely, you look at other countries like Ireland and Spain before the Eurozone crisis, which seemed to be perfectly fine, and yet the markets attacked them anyway.

I suppose the bottom line is that, while we can see the potential dangers building up here, as to when they will materialize we have no real idea.

ET: That’s the $57 trillion question as per the figure in that McKinsey report. It does seem that savers are surely facing some tough times ahead, with real and even nominal negative interest rates.

WW: Absolutely. As soon as you get into these kinds of scenarios where further damage is being caused to the health of the middle class that is already under severe pressure – you mentioned income distribution earlier – then you do have to think in a very serious way about what the social and political ramifications might be.

I mentioned before this group of researchers that included Martin Schularick. He began with a database documenting economic crises in a large number of countries over the last 100 years or so – a huge effort to pull this data together – and then expanded it to cover the political realm as well. He contends that after serious economic and financial crises it is very common to see a shift away from the political center, either to the left or the right. The left of course means more socialism and the right means more nationalism. The problem is that it’s all a big circle and you could end up with national socialism.

So we definitely shouldn’t understate the social and political ramifications from all of this.

ET: We’re seeing that in Europe and in the US, with candidates like Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Switching gears to the current macro picture, what is your assessment of the global economy? Are we going into a generalized recession or is the slowdown confined to some geographical areas and sectors? What is your number one worry in that context right now?